The Prestige, Illusion, and Nikola Tesla

Illusion and Wizardy

R.J. Carter in his review of The Prestige comments: “I love a good science fiction story; just tell me in advance.” In a similar remark from Roger Ebert, the film is “sawed in half.” On the one hand, it is a film about tricks and magic as illusion; on the other, it is about true magic or magic as wizardry. This thematically disconnected world is the primary interpretation of the film, and, if this is the case, the film is confused. Is this interpretation correct?

The film opens with its title card, “The Prestige”, and a field of scattered top hats. This is followed by Alfred Borden (Christian Bale), the protagonist of the film, asking the audience if they are watching closely. This is not a demand that the film places on the viewer but a suggestion. A suggestion that the film’s trick may be revealed to those with the desire and perceptive ability to find out.

John Cutter (Michael Caine) bookends the film with a description of the magical process. He tells the audience that “every magic trick consists of three parts or acts.” These acts are the pledge, turn, and prestige. The pledge establishes normalcy. The turn “takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary.” The prestige is the finale of the trick; this is where the magician “brings it back.” The world is returned to its ordinary state, but the audience is left with a sense of awe. By placing this description at the beginning and end of the film, the narrative is bound by this magical process. This is the film’s definition.

Cutter even prophesizes the audience’s response: “Now, you’re looking for the secret, but you won’t find it. Because, of course, you’re not really looking. You don’t really wanna know. You want to be fooled.” The film’s secret will be searched for in a superficial sense, but to uncover the true secret would mean a loss, a return to nasty reality. It will be energetically more favorable to stay in a space between complete foolishness and brutal realism.

This prediction is shockingly direct. It’s a statement that claims knowledge over the audience; humans are willingly fooled. One thinks that the immediate response to this should be skepticism and denial: “This may be the case for the foolish masses but not for me!” However, The Prestige’s trick is so convincing that it isn’t even considered a trick. Tesla is certainly a wizard.

Tesla Mythos

The core of The Prestige is a competition between two magicians. Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) is the better showman and the more materially prosperous magician. Borden is the “natural” magician; he understands what it means to dedicate oneself solely to magic. This difference is demonstrated in their responses to the Chinese man’s bowl trick. Borden immediately realizes the trick and recognizes the sacrifice and devotion to craft that is required. According to Borden, this total devotion is the only way to leave the material world, the only way to do something transcendent.

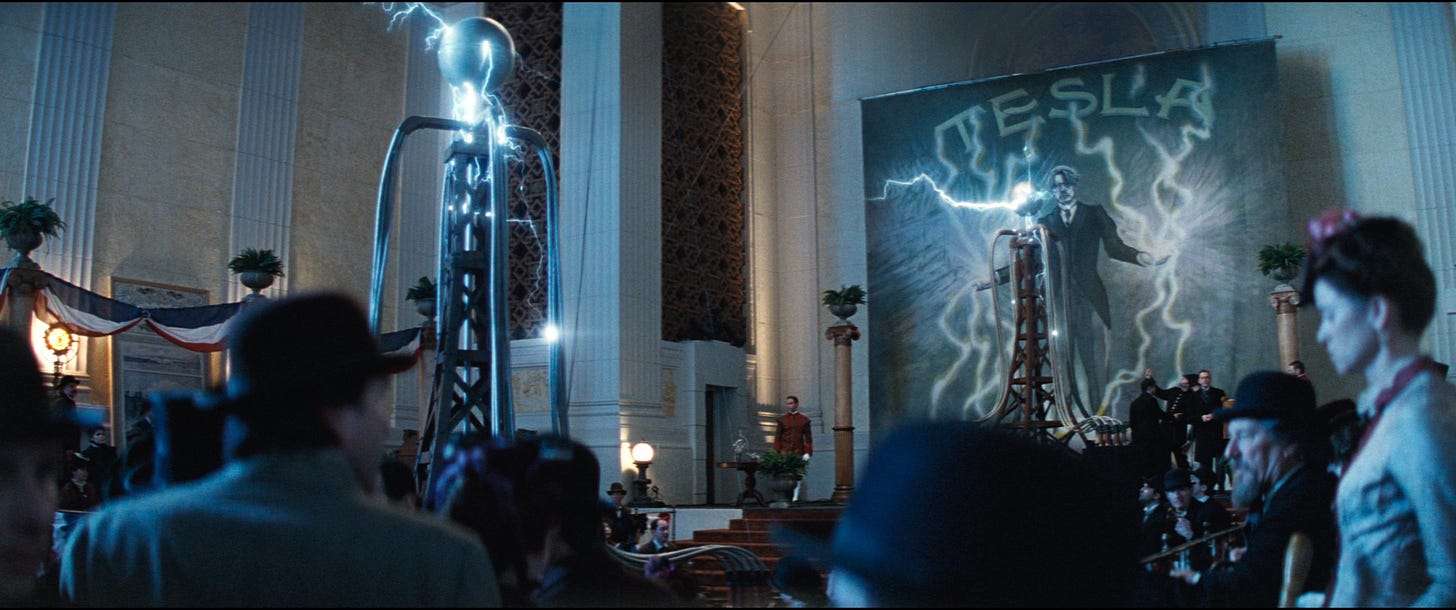

It’s clear that Angier is a skilled magician, but he doesn’t understand magic per se. He understands how magic works in the context of the stage but not in its transmuted forms. Angier is a naive magician, and he demonstrates this through his reaction to Tesla’s demonstration in London. He cautiously approaches the demonstration and gives a concerned look. Meanwhile, Borden sits beside the Tesla coil with a curious but confident stare. Borden understands that more than a scientific demonstration this is a performance. Show promoters extol the “miracle of Nikola Tesla.” Posters adorn the wall and display Tesla mastering electricity. Large arcs of electricity shoot between the two towers. Mr. Alley (Andy Serkis), Tesla’s assistant, assures the audience that everything is safe and any worries are the result of Edison’s smear campaign. In the end, the demonstration is canceled, but the performance is completed.

There is no greater symbol of the historical Tesla than the Tesla coil itself. It’s the inspiration for Tesla’s wireless power which he intended to power the entire globe with. The coil works by creating a magnetic field in the area around it which can induce an electric charge in nearby objects, and, therefore, light lightbulbs wirelessly. A concept that is used to this day in wireless phone chargers. However beautiful, the coil is a practically limited device and Tesla’s desire for global wireless power remains a desire. Nevertheless, wireless lives on in the form of low-energy radio waves that transmit information rather than energy.

Tesla more than a scientist was a visionary. In his acceptance speech for the Edison medal, Tesla attributed his knack for invention to a literal visionary ability:

“From childhood, I was afflicted in a singular way - I would see images of objects and scenes with a strong display of light and of much greater vividness than those I had observed before…When I turned my thoughts to invention, I found that I could visualize my conceptions with the greatest facility. I did not need any models, drawings, or experiments, I could do it all in my mind, and I did.”

In this description, Tesla appears like a religious prophet with mental ability exceeding that of a normal human. Like a religious prophet, Tesla’s wisdom is often provocative but unclear. In the essay “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy”, Tesla defines human energy as ½ mv2 where “v is a certain hypothetical velocity which in the present state of science, we are unable exactly to define and determine” and where “m”, the mass of mankind, can be increased by “careful attention to health, by substantial food, by moderation, by regularity of habits, by the promotion of marriage, by conscientious attention to the children, and, generally stated, by the observance of all the many precepts and laws of religion and hygiene.” For the physicist, this is pseudoscience par excellence. For others, this is demonstrative of Tesla’s unwavering individualism; someone interested not only in science but human well-being.

Tesla is perceived as a mythic figure. Like a myth, his history is stretched and altered over time. The Discovery Channel presents: “The Current Wars: Tesla vs. Edison.” This is a fictitious title, but represents the kind of stories that are presently told about Tesla. On the one hand, there is Tesla, the hero, and champion of unlimited free energy, and, on the other, the greedy robber barons, Thomas Edison and J.P. Morgan. These figures work to thwart Tesla’s development so that they can have a permanent monopoly over their profitable yet inferior energy.

This struggle even has an apocryphal origin story. According to this, Tesla was promised by Edison a fifty-thousand dollar bonus for completing some task. Tesla completes this task and demands the bonus, Edison denies him and comments that he must not understand the American sense of humor. An event like this does occur in Tesla’s autobiography, “My Inventions.” However, it's not Edison who gives the promise but some other manager at Edison’s company.

In Tesla’s exaggerated history, his rivalry with Edison culminates in the “war of the currents." However, the war of the currents was really between Edison and Westinghouse’s companies. Edison held patents for DC power and was beginning to lose development contracts to companies with AC. To regain control of the market, Edison engaged in an influence campaign that labeled AC power as dangerous. For example, Edison suggested that Westinghouse’s AC be used for the electric chair. Although Tesla did sell Westinghouse patents, the current war was more of a corporate war than a fight between two individuals. Like most good lies, there is truth in these mythic representations of Tesla. However, the truth is subtly changed to fit a narrative.

The Prestige interestingly engages with this mythos; these mythic representations of Tesla always come secondhand. Tesla himself speaks in generalities and platitudes. The Edison rivalry, unlimited free energy, and the current war come from Alley, the show promoters, and the hotel manager. Tesla himself makes no such statements but doesn’t deny them either. Tesla uses ambiguity to his advantage.

Tesla the Illusionist

Angier is obsessed with Borden’s transported man and is tricked into believing Tesla is the key to it. Borden can trick Angier by using his perception against him. Angier perceives Tesla as a technological wizard, and that is precisely how Tesla is marketed throughout the film. Alley is the business arm of Tesla’s operation; he procures funds so that Tesla can continue his research. Tesla and Alley are running a precursor to a venture capital startup. VC today is a minefield of scams and deceptions with the occasional diamond. Tesla and Alley are no different; they walk a fine line between genuine technological development and a scam.

Tesla can sell Angier an Illusion but not true magic. Tesla says exactly this: “If I were to build you this machine. You would be presenting it merely as illusion?” Tesla understands that Angier desires more than an illusion, and, therefore, ambiguously phrases the question. The question could imply that the machine is capable of much more than illusion or it could be a simple question about Angier’s intent. Angier, of course, believes the former, but Tesla could very well mean the latter. Tesla doesn’t tell outright lies; he is intentionally ambiguous and uses Angier’s perception of him to procure funds.

There is evidence that the historical Tesla did the same thing to his financiers. Tesla was often desperate for money to continue research into his wireless obsession. For example, Tesla received $30,000 from John Jacob Astor IV, owner of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, to develop a refined lighting system. However, Tesla quickly sank all this money into his Colorado Springs lab. After Astor cut off funding from Tesla, J.P. Morgan invested $150,000 into Tesla’s Wardenclyffe Tower which was an expansion of his experiments in Colorado. Tesla promised that he could transmit messages across the Atlantic in six to eight months. However, two and a half years passed and Tesla had nothing to demonstrate. In the meantime, Marconi had successfully transmitted radio signals across the Atlantic. This among other reasons caused J.P Morgan to stop funding Tesla. These cases exemplify a pattern of overpromising and underdelivering from Tesla; his reach often exceeded his grasp.1 How, then, was Tesla able to continuously procure funds?

The answer is the “miracle” of science. Science and technology expand human ability to the realm of fairy tales and myths. To ancient man, a jet could be a mythical flying chariot or an Angel sent from God. There is a gap between ancient man’s knowledge and perception. When prosaic explanation fails, humans turn to religion and magic because these are the only explanations left. Humans would rather poorly solve a mystery than leave a mystery open.

In the modern world, advanced technologies are the new religion and magic. In the words of Arthur C. Clarke, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” There is always the chance that a genius scientist could have an incredible breakthrough that would make the impossible possible. This is why the modern myth is the UFO, not the angel or demon. There are even several UFO religions including the Nation of Islam and Scientology. Advanced technology stands in for all unknown phenomena.2

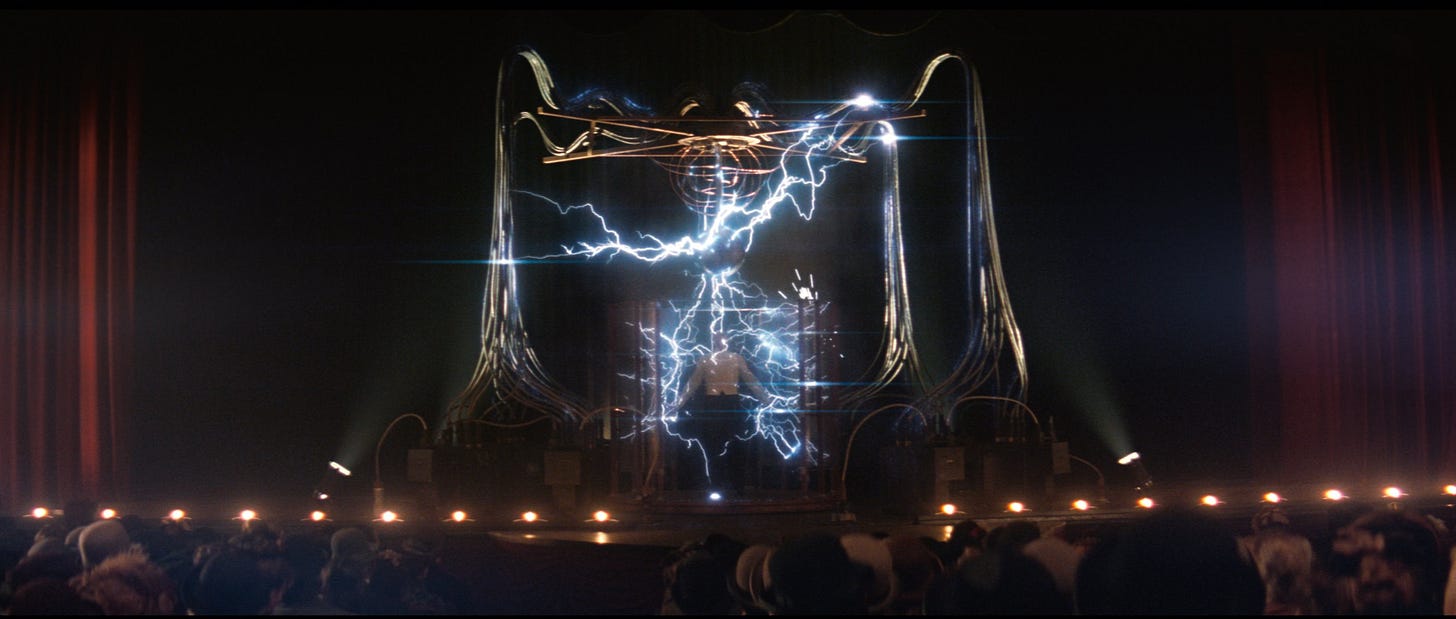

The historical Tesla and the Tesla of the Prestige walked a fine line between magician and inventor. Like a magician, Tesla’s three-part performance was “patent-promote-sell.” He would create an invention and then secure a patent for it. He would then make that invention “do something extraordinary”; he would go on promotional tours and extol the miracle of science. He would wirelessly light lightbulbs by using his Tesla coils. Audiences, stunned by this feat, would assume that if wireless lighting is possible then Tesla’s inventions must be capable of much more. They, of course, wouldn’t know that the extent of the technology’s known capability was given in the presentation. Finally, Tesla would bring it back to reality; the potential buyer could also take part in the miracle of science if they buy his patent, or, better yet, they could support him in developing something never before seen.

Techno-prophecy

Tesla was (and still is) a fascinating figure because he seemed to exist in the mystical “zone” between knowledge and perception, between reality and fantasy. Although Tesla’s feet were firmly wired to the ground, his mind was looking beyond, wirelessly. This is why Tesla is not just an overconfident salesman but, also, a visionary.

David Bowie fits nicely into this role of a visionary inventor, and Nolan is not the first to draw this similarity. Bowie also plays Thomas Jerome Newton, a humanoid alien who abruptly shows up on Earth, in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth. In the film, Newton is quickly able to amass a fortune by patenting advanced technologies that humans have yet to conceive of. However, the government fears Newton’s company’s growing technological advancement and forcefully removes Newton from the company. The government holds Newton captive and conducts experiments on him. One of these experiments involves X-raying Newton’s eyes which causes his contact lenses to be permanently fixed to his real, alien, eyes. After this, the government is no longer interested in him and Newton is free to go. However, Newton’s visionary ability is gone; he is left wealthy but creatively impotent.

The eyes are the natural symbol of visionary ability. It, therefore, makes sense that so much attention is paid to Newton’s eyes.3 A visionary requires this two-fold vision to see the world not only how it is but how it could be. Tesla’s vision of a wireless world is the world that currently exists but is a world that he never got to experience. Tesla, like Moses, never enters the Promised Land.

Prophets remain a part of the modern world but their prophecy is technological rather than religious. Techno-prophets like Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, and Sam Altman simultaneously divine and shape the future. However, there is a cheapness to their visions; there’s a sense that what could be is just an illusion. Similarly, Angier feels cheated by Tesla. He is given what he asks for but not in the form that he desires. Angier wants more than illusion. He wants Tesla to be a miracle worker and prophet. It’s clear from the critical reception of The Prestige that the audience wants this to be true as well. This is why Cutter’s prophecy is proved correct.

Angier’s Illusion

There are numerous reasons to believe that The Prestige contains no true magic. The best source of this is from the characters themselves. Angier admits this in his dying words: “The audience knows the truth. The world is simple. It’s miserable. Solid all the way through. But if you could fool them even for a second…then you could make them wonder. Then you got to see something special.” This is an allusion to the earlier fish bowl scene where Borden echoes a similar sentiment.

It’s therefore a reasonable belief that Tesla helped Angier develop an illusion and nothing more. His machine only shoots sparks at those who stand in it. It works as an illusion because advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic to non-scientists. Tesla uses ambiguous statements and Angier’s naive perception of technology to procure funding for his research. Tesla gives Angier what he asks for but not what he truly desires.

The only question left to answer relates to the mechanics of Angier’s illusion. Cutter informs Angier early on that the only way to do the transported man trick is through a body double, and, in every other iteration of the trick throughout the film, he is correct. This is the first clue. The second is the inherent flaw of the transported man trick. Namely, the body double has complete control over the magician. The body double at any time can blackmail the magician by threatening to reveal the trick's secret. Borden solves this, of course, through a body double that is just as committed to the trick, his identical twin. The way that Angier solves this problem is by “getting his hands dirty”; he murders the body double after each performance. The double presumably trains with Angier and falls into the water tank normally during practice; the double uses the trick door to escape the tank as demonstrated by Cutter in the opening scene of the film. However, during the actual performance, Angier uses a new tank with no such trick door and the double drowns to death. Angier chooses Borden from the audience knowing that he will eventually investigate under the stage. When Borden finally does this, the real Angier doesn’t show up in the prestige and therefore frames Borden for his murder. He disguises himself as Lord Caldlow (perhaps his real identity since he comes from money) and the rest is history.

This is the basic structure of Angier’s illusion but some interesting details make the illusion work. When Borden initially criticizes Angier’s transported man, he says that Root shows up “overweight, very drunk, and mute.” The first two problems can be solved by finding better body doubles. While this is possible, it will require a great deal of effort since Angier needs approximately twenty doubles. At the end of the film, there seem to be around twenty tanks presumably all filled with dead doubles. Only one body is ever shown, but this isn’t necessarily a significant detail. It doesn’t make sense that Angier would know the exact performance when Borden decides to go beneath the stage. Angier can’t read Borden’s mind and has to react to Borden’s actions. Therefore, Angier murders someone every night with the insight that Borden will eventually investigate under the stage. Angier needs to coordinate multiple body doubles for the trick to work. Furthermore, it is unknown how much time passes between his trip to Colorado Springs and his return to London. There could be a considerable period where Angier is traveling the United States to find potential doubles. Borden claims that Angier spent a fortune and traveled halfway around the world; this could reference just his trip to Colorado Springs but it needn’t.

The problem with this theory is that the double appears identical to Angier; there doesn’t seem to be a discernable difference. Nolan seems to be cheating here by using Hugh Jackman for both roles. However, this doesn’t necessarily ruin the theory, because Nolan “cheats” with Root as well! Both are played by Hugh Jackman, but the earlobe is used to discern between them. Angier has an attached earlobe, and Root has a free earlobe.4 Furthermore, Christian Bale plays the role of Fallon and Borden. Therefore, Nolan establishes the rule that doubles and originals are played by the same actor. This gives Nolan the ability to choose when he wants a double to be perceived as a double. This can be achieved through context and makeup choices. In Angier’s final version of the trick, Nolan doesn’t want the audience to notice these obvious distinguishing markers in the double but seems to want the audience to use the ideas of the film to discern the difference.

The final criticism that Borden mentions is the muteness of Root. A true impersonation requires a voice. This is why the most impressive part of a comedic impersonation is always the voice. The voice is somehow the gateway to another person’s essence. Furthermore, impersonations require a great deal of skill and practice. Therefore, it’s unlikely that Angier taught every double how to impersonate him perfectly. It would be much easier to teach the doubles how to mouth his words properly. At a certain point in the trick, the Angier double no longer speaks to the audience. He allows audience members to investigate Tesla’s machine as he stands silently. Furthermore, the Angier double only speaks from a certain position on the stage. The real Angier could be somewhere out of sight performing through a speaking tube. Once the speaking portion of the trick is done, Angier rushes up to the balcony for the prestige. It even seems like Angier is panting during the prestige which further indicates that he needed to run up to the balcony. This may not be the exact method that Angier uses, but some kind of acoustic manipulation is likely going on.

Acoustics are an essential aspect of the performing arts. Ancient Greek and Roman amphitheaters manipulate sound waves so that the sound source is perceived as closer than it is. This allows the audience, even those in the “nose bleeds”, to feel more immersed in the performance. In modern cinema, “surround sound” creates the perception that the audience is in the middle of the action. Sound is crucial to convincing an audience that a world is real or, in the film’s case, that a trick is real even though it's not. Nolan is no stranger to sound illusions. He often uses Shepard Tones to create the illusion that there is a constant ascending tone. In The Prestige, he uses it in the track “Colorado Springs” to create a mysterious atmosphere.

In the end, these theories are all speculation. The audience doesn’t get to go backstage for this illusion. Its true nature is largely a mystery. However, the world, in a thematic sense, is more coherent if Angier’s final performance is an illusion like the rest. Although it’s alluring to see Tesla as a true magician, he too is an illusionist. Everyone in the film is grounded in the same solid reality.

Historical examples are from “Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age”

There is a growing trend of positing an ancient lost civilization with advanced technology to explain amazing feats of ancient architecture like the pyramids in Giza.

This two-fold alien and human vision is perfect for Bowie who has a permanently dilated pupil.

In the version of the transported man with Root, he emerges from the door with attached earlobes, and then seconds later during a closeup shot Root has free earlobes. It could just appear that way due to distance, but it certainly seems to be attached. Furthermore, it only becomes clear that it’s a double when the camera leaves the perspective of the audience and enters a personal “in on the trick” shot. Nolan may subtly cheat here to contrast the audience’s perspective (the audience of the performance, not the film) and a behind-the-scenes perspective.